Resupplying Tomorrow’s Battlefield

Future-Proofing the Force: Next-Gen Resupply Solutions

The future of battlefield resupply will be even more challenging against a near-peer adversary when compared to the wars fought in Iraq and Afghanistan. Contested air space and advanced, long-range weapons could make traditional logistic resupply by truck an even higher risk. In response to this challenge, the Army is considering drone technology as a possible answer. Unlike with many technologies of the past, it is the consumer market, not the military, which appears to be ahead of the curve. And while driverless technology from commercial firms like Google have evolved rapidly, this does not translate into ground-based operations given the need to travel off-road. This has been confirmed by the Pentagon that autonomous resupply by air will happen before ground vehicles. With this in mind, the Pentagon has turned to the drone logistic industry for possible solutions to safely and quickly re-supply our Soldiers on the battlefield.

Advancing Commercial Drone Delivery

The FAA has predicted that by 2023 the commercial drone market will triple to near one-million aircraft. This isn’t mere speculation; the agency is actively involved in the sharp incline of drone use in the private sector, announcing in August of last year that they will be giving $7.5 million in grants to universities, intended for research on “the safe integration of drones into our national airspace.” In the immediate sense, consumer giants, such as Google, Amazon and UPS, have already made the first steps towards fully autonomous supply chains in multiple U.S. markets, as well as abroad. The recent coronavirus epidemic has only accelerated this process.

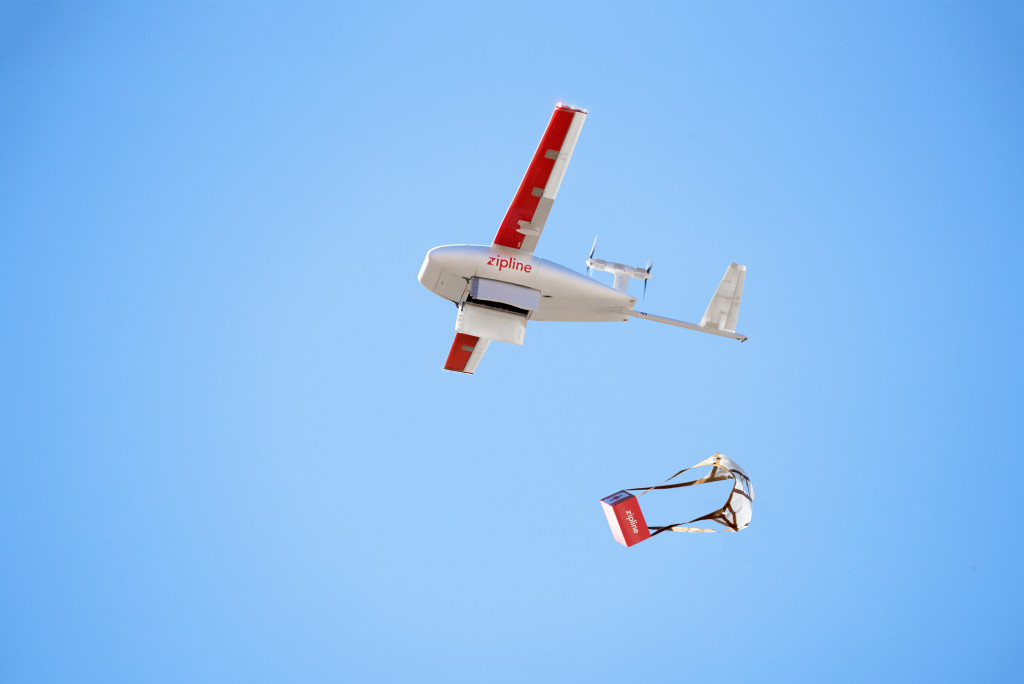

Figure 1. Zipline drone delivering medical supplies.

In March of 2020, Zipline, which got its start delivering medical supplies in Rwanda, partnered with Novant Health to deliver medical equipment and PPE in North Carolina (Figure 1). Their drones made thirty-two-mile flights from Novant’s fulfillment center to their medical center to assist frontline workers. Also in the drone logistics race is Alphabet’s (Google) drone program, Wing, which was the first company to receive FAA approval for drone delivery. In 2020 they partnered with Walgreens to make local prescription deliveries truly contactless and get critical medication to individuals in lockdown. Seeing as Walgreens has a store within five miles of nearly 80% of the US population, the Wing can potentially deliver a wide range of products throughout the country. Amazon’s Prime Air continues to inch closer to a wider rollout. With it now receiving FAA selection to participate in certification for drone delivery, it will only be a matter of time when the “30-minute delivery” and “less than 5 pounds” restrictions are lifted. One interesting difference Amazon is making with its drone program is the filing of patents for a new surveillance system. An Amazon drone could, in essence, become an intelligent security camera to check for potential security issues of the home. This could be an interesting dual-use feature for the military.

Drones and the last mile

While the scientists and engineers work tirelessly to advance drone technology, supply chain managers are already looking to implement drones to overcome current logistical hurdles. In the supply chain world, a product's travel from the warehouse to a customer’s home is referred to as “the last mile.” It represents, by far, the shortest transit distance. Yet, due to multiple stops and typically smaller parcel sizes, the last mile accounts for over half the total cost of delivery. In sprawling rural areas, the problem arises from the distance between individual drop points. In more urban areas, the opposite is true as congestion and bottlenecks present their own hurdles. This problem has plagued the industry for decades, with managers and analysts reconfiguring processes to shave mere pennies off transit costs. Drones, even with their currently limited range, can make the final leg of deliveries at just $0.05 per mile, according to research from the Deutsche Bank. This represents a solution that is both fast and cheap, two things that have long been considered mutually exclusive in supply chains. Using drones to mitigate the challenges of resupplying troops in remote and austere environments can bring the same “fast and cheap” benefit seen by large logistic companies. But there are challenges!

Figure 2. Operator manually swaps battery pack in Zipline drone.

Both Zipline’s and Wing’s new programs are almost certainly indications of what is to come in the consumer market, though there remains one glaring issue, namely, the range of modern drones.

Batteries, specifically run time and recharging, continue to be the weak link in the future of drone delivery. And in some cases where rapid re-charging stations are not available, technicians are having to “swap” out depleted battery packs with charged versions (Figure 2). Drone systems that require a large amount of human interaction can make this technology impractical, especially for remote environments. What are tech giants doing to solve this issue and accelerate drone delivery adoption?

Solving the Range Solution

Incorporating drones into last-mile delivery represents an immediate solution to an age-old problem, but the commercial market does not view this as the end goal, and neither should the military. The future is certainly fully autonomous supply chains, with long-range drones as the primary fixture. The steady improvements of battery technology aside, the Amazons and FedExes of the world are still set on more radical solutions, such as in-flight recharging. Using high-power charging technology, companies are developing stations that can charge multiple drones from meters away with an output of twelve kilowatts.

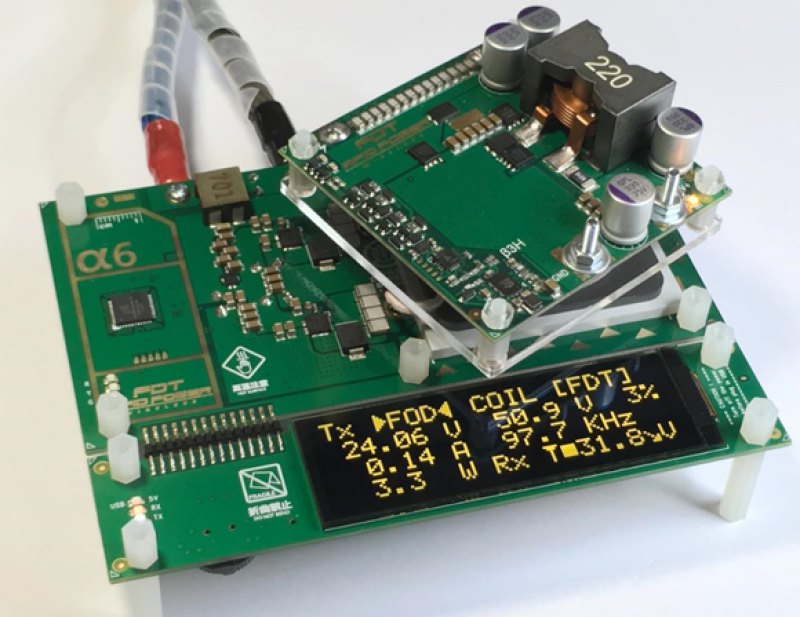

Figure 3. Xentris Wireless has integrated 300W wireless technology.

A network of these stations could make a drone’s total flight time indefinite. In addition to in-flight charging, several logistic giants have begun investing in drones capable of generating reliable energy from the sun. These lightweight and thin-film solar cells claim to have a solar cell conversion efficiency upwards of 29%. This is a technology that can be installed directly onto the drone, assisting in both weight and aerodynamic hurdles as well.

Wireless charging is the key to removing the need for human interaction. It quickly becomes impractical for an operator to connect dozens, if not hundreds, of charging cables. And while in-flight charging and mounted solar cells show promise, inductive charging continues to hold the most potential. While the Qi standard is currently limited to 15W, Xentris Wireless has implemented higher wattage systems that are ideal for wirelessly charging drones without the need for cables or wires (Figure 3). And while there is no way around the market to push the bounds of current battery technology to expand drone range, contactless charging is the key to adoption for using drones in both the commercial and military markets.

An Image of the Future

Figure 4. Bell’s Autonomous Pod Transport (APT 70) can deliver 70 lbs. to Soldiers on the battlefield.

The concept to use drones to resupply troops on the battlefield has been around for a few years but has gotten more attention from the military. Army Futures Command (AFC) developed the “Joint Tactical Autonomous Aerial Resupply System” (JTAARS) about two years ago with the hope of getting the system in the field by 2026. Besides requirements for longer flight times, being autonomous and quick set-up, the Army requires that these drones be able to navigate in GPS-denied environments and hardened against cyber-attacks. And as the commercial sector continues to invest in the drone delivery market, systems designed for the task will become more reliable, more capable, and less expensive, likely benefiting the U.S. military. The U.S. Army is now formally asking industry for information on supply drones as part of the JTAARS program. This system promises to lighten Soldier loads and allows commanders to control delivery timing of mission-critical supplies and equipment. Also, Bell’s Autonomous Pod Transport (APT 70) is an autonomous vehicle that can now carry payloads up to 70 pounds. This is equivalent to 36 MREs, 72 water bottles and 64 magazines of 5.56 ammunition.

With fully autonomous supply chains on the ever-approaching horizon, there is most likely not one simple answer on how to fully incorporate the modern drone onto the battlefield. It will require a combination of all the options previously discussed. But one thing is for sure, without a support infrastructure in place that reduces the need for human interaction, drone delivery of supplies to our troops quickly becomes impractical. Fast charging, high-power, wireless charging is a key component to assigning drones to handle last-mile deployment of materials to Soldiers.

Quick adaptation of rapidly advancing drone technologies is already being used in the private sector. Tomorrow’s battlefield will be one that is efficient, secure, and further protects the Soldier by removing them from exposed convoy chains.

Figure 5. Soldiers of the 3d U.S. Infantry Regiment (The Old Guard) receive supplies from a Joint Tactical Aerial Resupply Vehicle (JTARV) on Fort A.P. Hill, Va., September 22, 2017. (U.S. Army photo by Pfc. Gabriel Silva)

With industry-leading expertise in power delivery and fast charging technologies, Xentris Wireless is poised to deliver both higher capacity batteries and better-charging solutions.